|

|

|

|

|

| Magdalene Laundry |

Dr Francis Moloney

Trafficking Bodies from the Ancient World to the Present

Graduate School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry

Research Essay Assignment May 17, 2019

|

|

Slavery has many components. Metaphorically it is an historical pie chart: dominated by large slices of

long forgotten Roman captives, and recently remembered exported Africans.

Australasian slavery occupies a narrower strip which is itself subject to vigorous debate as to its being accepted as

true slavery.

That less well-defined segment includes indentured and unindentured Aboriginal labourers, South Sea Islanders 'blackbirded'in

the 1890s, a generation of stolen children, and incarcerated single pregnant women awaiting the forced adoption of their offspring,

in modern times.

This essay examines the exploitation of those Australian women, used as involuntary and unpaid labourers before their

gravid;'middle passage'; to the obstetric suite for delivery of living human cargo into the hands of adopting married couples.

As a nine-year-old pupil at Wooloowin Convent, the writer witnessed daily the forced march of a bevy of females with large

bellies, monitored by their Sisters of Mercy guards from the nunnery to the laundry. Although not yoked together in shackles,

those young women were linked by bonds of unplanned pregnancy and uninvited custody; all closely supervised by unforgiving,

if well-intentioned, authorities.

One cannot imagine the everyday experience of those convent-controlled expectant mothers.

That schoolboy of the late 1940s remained ignorant of the sequestered world beyond the schoolyard fence. Meters away toiled

the detainees of an era of rigidity and conformity, emblematic of the patronizing society which had enforced their internment.

Theirs was an historical landscape where the Law condoned the actions of those Nuns, and of similar charitable organisations,

permitting the trafficking of new-born children.

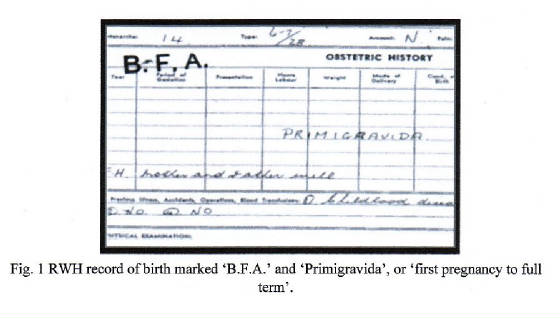

Those dealings were veiled in secrecy and underwritten in obfuscation and in an encrypted language. A baby for adoption

was an abbreviated;'B.F.A.'; stamp on a birth record: three letters promising the new child a life of potential happiness,

but a future enveloped in a fog of uncertainty.

For many it involved an incessant search for answers of identity, which answers might partially assuage their sense of

not belonging.

As adoptee Barry Ford described;'a few years ago I attended&;' [a family]& funeral' and asked my cousin if she

was aware of my adoption; she replied that everybody;knew but me;' 'I was not impressed'.

Ahead for many was the discovery that they were;others; part of a family, but not quite. Hidden was a birth-mother whose

body had been imprisoned, and the product of her gestation purloined for a; better purpose;

For most adoptees, better was illusionary and potentially untrue. In Annettes words;'disbelief that I had been lied to

for my entire life was the overwhelming emotion that penetrated my being'.

Annales Historians concentrate on a place, an event or an individual, thus allowing the wider scene above to be viewed

more clearly through the micro-historical lens below. Marc Bloch espoused 'that the historian'first duty is to be sincere.

With sincerity, therefore, Lily Arthur (née McDonald) is the subject, and the Annales approach, the technique used here

to investigate the history of her emotions as an enslaved woman awaiting release.

Her kindred sub-class was subjugated by the unbending and misogynistic actions of a paternalistic Government and its willing

agencies. Lily's tale moves from the ignominy of an almost seventeen-year-old minor, arrested for;living immorally; in 1967,

to a national apology in 2013.

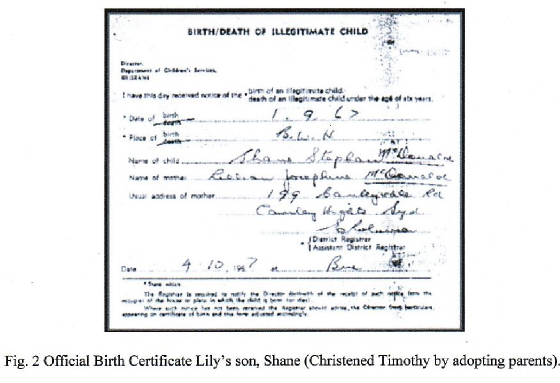

The ensuing financial compensation was widely criticised as token and inadequate. Her twenty-year-old male partner was

given a Police warning. In between those extremes was a baby son, Timothy, delivered from Lily's body as a product of her

uterus, and handled as a commodity for social usage.

Consistent with all trafficking transactions, money was exchanged. Five dollars was paid by the new parents to the Nuns,

for the privilege of taking Timothy home. Lily's document of manumission was a hospital discharge summary.

She returned to freedom without the grace of a traditional Afro-American or Afro-Caribbean slave's apprenticeship period

to adapt to her new environment.

She describes her feelings as 'chastened, humiliated, and seething with anger'.

For Lily the contagion of liberty, so feared by slave-owners of the past, would in modern parlance,go viral; in its long-term

implications across Australian society for generations to come.

Reminders of the remainders of the dead take a variety of forms...[and]...their meaningful survival...requires a social

basis and historical memory which, once lost, can be difficult if not impossible to recover.

Praying to a relic can work miracles for, or provide some improvement in the life of, the petitioner.

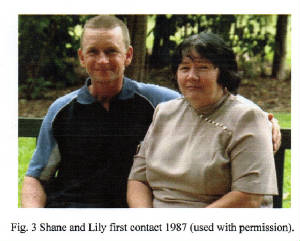

Lily's orison was answered with freedom of information and her reliquary was a manila folder in which she preserved her

son's birth records, excavated doggedly over twenty years from the depths of well-hidden archives.

Evidence exists that successive Governments passed laws which would be construed in 2019 as attempts to impose strict

standards of morality on single mothers, but in keeping with accepted social mores of the time. Those cloistered unwed pregnant

women underwent a managed psychosocial metamorphosis from people to the equivalent of domestic animals.

One can extrapolate from the work of Jeremy Clark that those convent inmates experienced the same sense of dehumanisation

that was common to all enslavement practices and was essential for the transition of a captive into the hapless state of a

slave. Thus, Lily's situation was mediated through [her]'subordinate status and brutal exploitation as a commodity;'

Don't touch him girl! He is going to a good home' was an unambiguous directive from a Midwife, supervised by a Social

Worker, in the early-1970s, to the newly-delivered and involuntary baby-donor.

Did the Midwife understand the sociological nuances of agency, thus ensuring that free choice was not an option; not even

a few seconds of first contact? The child was removed immediately after delivery and taken to a locked nursery.

For Lily it was bewildering and devastating; no tit, no touch, no transitory glimpse of the neonate. The primigravida

was now alone in the world, her habeas corpus, or sense of possession of her own body, altered irrevocably and her sense of

proprietorship of her offspring a momentary reflection.

A Psychiatrist might conclude that Lily would remain prone to a perpetual sense of disownership, the main étrangère of

the amputated hand, replaced by the bébé étrangère of the traumatised mother.

Undoubtedly Lily's treatment in 1967, was based on historical precedent, with Government agencies acting legally. In 1887,

the Benevolent Society of New South Wales debated the ethical dilemma of mixing primigravida single mothers with their more

sinfully-indulgent multigravidae associates in maternity wards.

The first-timers must be 'set apart';[from]single women confined more than once;as the effect of such association might

possibly prove pernicious;

In 1890, Melbourne's Coroner, Dr Richard Youl opined that;every single woman in the colony, directly she found herself

pregnant should so officially register herself, and the neglect for so doing be punishable with an imprisonment of say two

years. Nine-tenths of unmarried mothers come from the servant-girl class. Those of that type are invariably thriftless and

of a low standard of intelligence... reported Edward Maxted in 1894.

Aristotle would have agreed: such women belonging to his physei doulon or servile-by-nature societal substratum.

Not all Australian authorities in 1901 treated single, pregnant women so dismally: The Salvation Army remaining their

sole provider of 'no frills' charity. 'Why should a poor girl have a millstone of ostracism hung around her neck'while the

man is accepted into society without a blush?

Their Chaplain added 'the Army provides every comfort for unfortunate girls in trouble;' and generally does more practical

good in one week than fashionable religion effects in a 12 month [sic]; Equally pragmatic, the National Council of Women

considered the question of how a suitable home, and employment for at least twelve months, could be provided for unmarried

women and children;

Some States were sympathetic, the Superintendent of the Children's Department in South Australia reporting, after an extensive

research trip in 1911, that he was impressed by a country home for the reception of unmarried women and their children;[where];

there was a desire that mothers should remain resident and look after their infants for as long a period as possible.

1912 saw not-unexpected resistance to such humanitarian considerations, when the Council of Churches issued a warning

that Politicians were treading on dangerous ground.

It sent a deputation to Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, railing against the payment of Maternity Bonus [sic] in cases where

it is known that the child is illegitimate;[such action being]; 'incitement to immorality.'

A decade later, The Mothers Union and Benevolent Society tabled a demand in a 1927 Royal Commission hearing; that the

unmarried mothers should;[not] be placed on equal terms with respectable married women.

When the original newspaper report of that years National Council of Women's Conference is read thoroughly, however, it

is apparent that the statement above had been 'cherry-picked' for its negativity, and represented the reactionary voice of

a minority of delegates.

The minutes are replete with sympathetic cries supporting illegitimate children, arguments to legislate for their inheritance

freedoms, their rights to a good education, and especially for the Government to define more clearly the financial and moral

responsibilities of the father.

The father-figure is rarely mentioned in those early debates. It would seem that even in the 1920s, the laundry was the

common temporary abode of the single, expectant mother, Lady Allardyce eliciting general laughter from the audience [when

she];defied any of them to stand all day in a steamy laundry and want to be good.

The Adoption in Australia web site provides detailed accounts of societies vacillating attitudes from the 1880s to 2019,

based mainly on old newspaper reports and recent State and Federal Parliament's legislative procedures.

The slow evolution from kind thoughts (but harsh reality) to a permanent transformation in how to manage the emotionally-charged

subject of forced adoption, was due almost singlehandedly to the primary focus of this essay, Lily Arthur.

It commenced with her submission to the Senate Inquiry into Stolen Wages in 2006. There followed a separate inquiry into

forced adoption practices, and the eventual apology in 2013. Between 1950 and 1975 there were between 210,000 and 250,000

forced or coerced adoptions, defined as 'where a child's natural parent, or parents, were compelled to relinquish a child

for adoption'.

It must be conceded that amongst that population were many who agreed with the arrangements made on their behalf. Their

uncomplaining voices remain unheard, and their exact numbers unknown.

But is there a counter-argument that Lily Arthur and her pregnant cohorts were never really slaves? Is legally-enforced

domestic servitude classical slavery? Orlando Patterson provides the answer.'The slave was natally alienated and condemned

as a socially dead person;[her]; existence having no legitimacy whatsoever'.

Additionally, the process of incarceration assured that Lily and her ilk would experience at the very least, a secular

excommunication. For an ultimate refutation of the counter-argument: res ipsa loquitur, courtesy of the excommunicant herself.

I was unlawfully arrested having committed no crime under criminal law; I should not have been under the care and control

of the State;at the age of sixteen years and eleven months I was over the age of consent and living in a de-facto relationship

with the father of my child with whom I had intentions to marry; I was placed into;[Wooloowin Convent];by the Children's Court

where the State knew I was going to be put into slavery and forced to work without payment, a breach of the Queensland Children's

Services Act 1965; the reward for working in the laundry was thirty cents worth of lollies on a Friday any misbehaviour saw

the privilege removed.

In 2004 I applied for the wages due to me;[but was told] there was no provision for wages[for] girls under 'care and control';I

could not freely receive advice from counsellors, social security and welfare agencies; my baby was taken from me straight

after the birth;[and] placed in a locked nursery; I signed illegally adoption consent under threat of further imprisonment,

for a baby whose sex was informed to me anecdotally and [whom];I had not seen;the lack of accountability of the State of Queensland;

is an insult to the notion of common decency;whereby no one is exempt from criminal prosecution if they have knowingly breached

the law.

Lily Arthur's tenacity and steadfast determination to expose past adoption practices benefited many individuals and families,

her actions comparable to those of abolitionist pioneer Thomas Clarkson. His ground-breaking use of primary sources to support

arguments condemning slavery in eighteenth-century England was mirrored by Lily's painstaking research and meticulous gathering

of personal records in twenty-first-century Australia.

Her submission to Parliament was universally accepted and unreservedly endorsed.

Her singular focus and perseverance were rewarded with a gradual mellowing of community attitudes. Forced adoption will

remain, like the bondage practices of old, a memory of a time and of a society, behaving in a manner it believed appropriate.

Such practices are now viewed through a more transparent and more enlightened lens.

Those Nuns and Midwives were not evil people, despite our 2019 perspectives. Unfortunately, the slavery pie-chart has

not been completely erased of its constituent pieces. Sex slavery in Australia, together with child-labourers aboard, and

indentured workers on many continents, continue as a significant blemish on its surface.

Thanks to Lily Arthur and the many thousands she has inspired, forced adoption in Australia is now nowhere to be seen.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

'Adoption of Children Act 1935'.Find & Connect. Accessed April 27, 2019. https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/qld/QE00016/.

Arthur, Lily. 'Inquiry into Stolen Wages'.; Origins Australia (Forced Adoption Support Network). Accessed April 27,

2019. https://www.originsnsw.com/index.html/.

Submission into Stolen Wages: Slavery and Child Exploitation in Queensland; Parliament House. Accessed April 28, 2019.

https://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/../

stolen_wages/submissions/sub02_pdf.ashx/.

Bruntnell, Albert. 'Religion Without Frills'. Cairns Morning Post, June 18, 1901, 2.

'Forced adoptions History Project'; National Archives of Australia. Accessed April 17, 2019. https://forcedadoptions.naa.gov.au/content/overview-forced-adoption-practices-australia/.

'History Timeline of Adoption in Australia 1880s to Present'; Origins Inc.. Accessed April 26, 2019. https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=a70034e9-001a-48f7-9267/.

Longmore, James.'State Children and Charities: Observations in the East'. Western Mail, May 6, 1911, 2.

Maxted, Edward. 'Benevolent Society of New South Wales'. The Sydney Morning Herald, August 18, 1887, 4.

'The Increase of Poverty in Sydney: An Interesting Return'. South Australian Register, June 13, 1894, 6.

'National Council of Women'. The Hobart Mercury, January 20, 1922, 6.

'No Bar'.1; Northern Territory Times and Gazette, September 5, 1912, 3.

'Overview of forced adoption practices in Australia'. Forced Adoption History Project. Accessed April 27, 2019, http://forcedadoptions.naa.gov.au/content/overview-forced-adoption-practices-australia/.

Stone, Mary Page. 'National Council of Women'. The Melbourne Argus, February 25, 1910, 4.

'The National Apology for Forced Adoptions'. Attorney-General's Department. Accessed April 17, 2019. https://www.ag.gov.au/About/ForcedAdoptionsApology/

Pages/default.aspx/.

Youl, Richard.'Child Murder and Baby Farming'. The Brisbane Courier, December 18, 1889, 7.

Secondary Sources

Ambler, Wayne. 'Aristotle on Nature and Politics: The Case of Slavery'. Political Theory 15 (1987): 390-410.

Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press,

1967.

Bloch, Marc. 'The Historian's Craft'. Caravelle Vintage Books ed. New York: Penguin Random House LLC, 1953.

Clark, Jeremy. A Brief History of Slavery: A New Global History. London: Constable & Robinson, 2011.

Clarkson, Thomas (1760-1846).BBC History. Accessed April 27, 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/clarkson_thomas.shtml/.

de Vignemont, Frederique. 'Habeas Corpus: The Sense of Ownership of One's Own Body'. Mind & Language 22 (2007): 427-449.

Gone to a Good Home. Directed by Karen Birkman. Canberra: National Film School of Australia, 2005. Single-Layer Disc.

Moore, Peter. Earthly Immortalities: How the Dead Live On in the Lives of Others. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2019.

Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press,

1982.

Quartly, Marian, ed. The Market in Babies: Stories of Australian Adoption. Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Publishing,

2013.

Shapiro, Susan P. 'Agency Theory'. Annual Review of Sociology 31 (2005): 263-284.

APPENDIX

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For an original copy of this essay

Contact The Author

Dr Frank Moloney KHS, BDSc (UQ 2nd Hons), MB BS (UQ 1st Hons), FRACDS, FRACDS(OMS), FFDRCS (Irel),FACOMS, FICD.

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon

Visit our Facebook

|

|

|

|